Cornish Miners Memories 4: Former South Crofty Miner Mike Ricks has kindly written a piece about his time underground. My thanks for allowing me to publish it on this page. Cornish Miners Memories 4

Three Years Before The Eimco.

In March 1970, fresh out of the Royal Navy, I was sitting in a friend’s Mini, disconsolately watching the cold winter surf at Porthtowan. Herbie Hattam, Surf Club captain and South Crofty mine captain, were chatting through the window. He suggested I try his mine for a new line of work. That prompted me to go see Howard Mankee, the legendary captain at Cook’s at South Crofty Mine on a Friday afternoon.

All he suggested was that I ‘bring a flask, and a coat as it’s cold when ee’ come up’, and I was hired. As I left I saw what appeared to be a gang of pirates in ochre-stained rags emerge from the shaft cage. I had no idea what I was getting into.

I slept badly that Sunday night. Constantly checking the alarm clock, as I had to rise at an ungodly hour and ride the 10 miles or so to Pool in the black pre-dawn on my mother’s Honda 50. Cook’s side ‘dry’, the change room, was chaotic as men found their work clothes and boots. Despite the hostile stares someone took pity on me and found me a belt and helmet lamp.

I was shepherded to the shaft cage and we slid down in the pungent warmth of the shaft. Down 360 fathoms to Cook’s side of this centuries-old tin mine deep in the granite of Carn Brea. My first day was helping hang an air-driven fan and ventilation tubing in a tunnel that felt like a tropical swamp. Ggasping in the hot fog it appeared that ventilation only became an issue when conditions reached an almost unbearable level.

So began my first week as an OC, standing for Ordinary Contract. The small gang of odds and sods on a basic wage, as I remember about £20 a week. Also the price of my new boots was deducted from that. We were used to move stuff around. Either pushing a mine car bogie, or the chassis of a one ton mine wagon. Often loaded with pipes or timber or supplies for miles along deserted tunnels to distant work places. When that was done we cleaned up and dug drains along the tunnel sides to help the flow of water. It was painfully slow with only pick and shovel, for a little bonus.

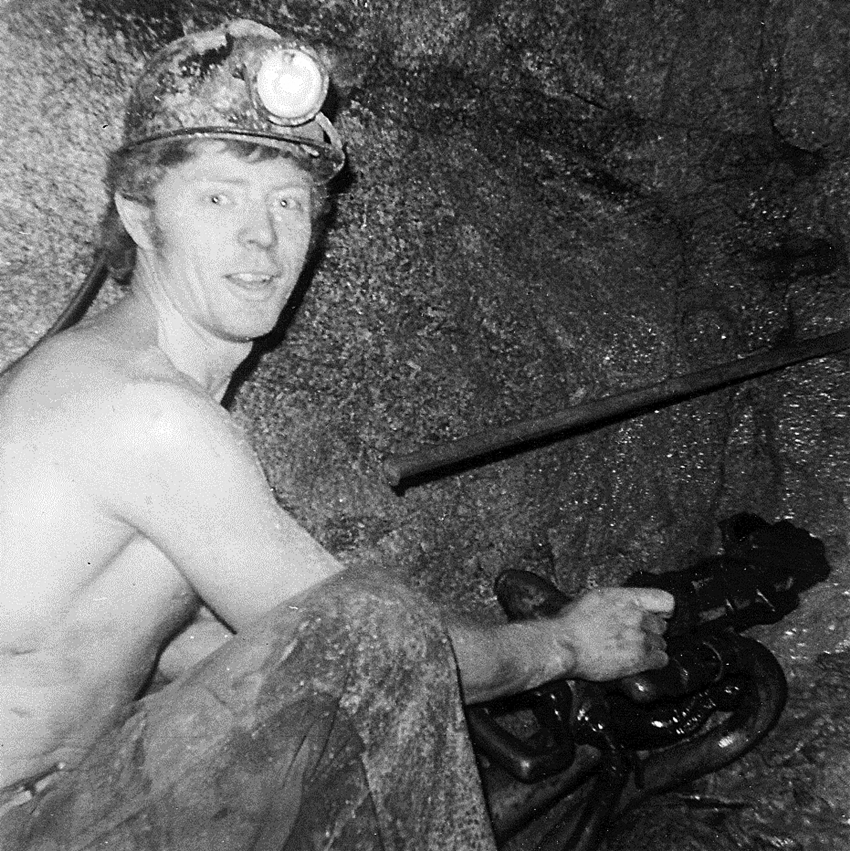

The country might have gone to decimal currency but our bonus for a drain was still set at a shilling a foot. All this activity was carried out stripped to the waist in the perpetual steamy summer of deep underground. On the Friday of that week I spent the day breaking up rocks on a grizzly on 290 level with another new boy. Swinging a sledgehammer like convicts, and standing aside as a trammer arrived to dump more.

Coming up each afternoon I showered under a thin trickle of hot water. Then hung my wet clothes on steam pipes, hoping they’d still be there the next day. Herbie Hattam must have taken pity on me as I was moved to Robinson’s Shaft side for the following week.

Robinson’s side had a newer dry. The shaft there was downcast, as opposed to the upcast Cook’s shaft which vented the foul wet air from below. The dry had heated lockers for wet work clothes and decent showers. Whilst on the subject of showers we all toddled round naked between locker and shower. It was normal to get someone in the next shower to scrub the ochre off your back. The older miners wore a cotton cap under their helmets and these doubled as wash cloths.

Once again I was on the OC gang. Doing whatever the amiable old shift boss, Vernon Salmon, had in store for us each day. Sometimes in the middle of the day we would skid mine cars loaded with ore across a steel plate into the man cage to supplement the main ore hoisting at Cook’s side. The skilled miners were known as machine men. Each had their own workplace, be it a drift, raise or stope, where, with a younger man for help, they drilled and blasted. We OC’s occasionally were sent in to help when their regular partner was absent and my turn came in my second week. Cornish Miners Memories 4

On the Friday of my first week on Robinson’s side I followed Dennis Roberts to where he was raising. Driving a tunnel up at about 50 degrees inclination I soon learned my function in life as the drill steels on my shoulder bit into me on the long trek in. We probably had a five minute sit down at the crib seat, a plank with a backrest that was rarely enjoyed, before Dennis was up and at it. I kept out of the way while he climbed up, gingerly shaking the single chain for loose rocks, then up I went with two steel pins, down and up again with two thick planks, down and up again with more gear.

The raise was already about 150′ up but the darkness seemed to reduce any sense of the void below, or maybe it was just blind faith. Dennis barred down any loose slabs of rock. Found by the drumming noise when hit with the pinch bar. He yelled down again for the water hose to wash down the grit and dust any wash out any sockets that might hide unexploded gelignite. Then a rope came down for the rockdrill and I went up with it, boosting it upwards. My boots scrabbling on the grit, by now every capillary and pore in my overheated skin on overdrive.

Up again with the airleg, airhose and drill steels. Then when all was set up I went down to turn on the air and water. I joined Dennis as he balanced the rock drill on its telescopic leg on a narrow platform high above the dark abyss of the raise. Indicating a narrow ledge just above the stage he told me that was my place for the day. I had to hold the chattering end of the drill while he collared the hole. Water flying like a tap and when it was safe to do so he slammed the rock drill on full. The roar was unbelievable in the narrow confines of the raise. Knowing it was my first taste of steel, Dennis wasn’t holding back.

Two hours of standing under a stream of water and grit hopping from one foot to the other. Later, and mostly deaf, the round was drilled, maybe some forty or more holes four feet deep. The worst of all being the back, or top, holes with the rock drill poised above our heads and hard to control. Last but not least the rock drill was disconnected from the airleg. Then shoulder to shoulder, leaning on the kicking and bucking drill when I thought every bone, muscle and tooth was being shaken loose. We put in two short holes for tomorrow’s stage pegs.

No reprieve yet for I had to scramble down.Then hoof it back to the shaft station for whatever number of sticks of gelignite and wooden spacers that Dennis had calculated he needed. Struggling back up the raise with everything we commenced to charge up the holes. A stick of gelignite with an electric millisecond delay carefully filled up the hole, easing its thin wires in with it. Each hole was loaded with gelignite to the collar. Then tamped in with the wooden stick, and the charge in some of the back and side holes reduced with wooden spacers like sticks of kindling. Then it was plugged with a wad of wet cardboard torn from a gelignite box.

Finally all the gear came down and Dennis descended unrolling two spools of wire and connected up to the thicker blasting cable. No time for lunch or a cup of thermos coffee, the day’s activity would have taken us close to time to catch the cage. We gathered up clothes and bags and retreated back down the tunnel to the other end of the cable. Faint crackling would be heard at this stage of others blasting. Dennis wound up the Beethoven exploder and produced our own crackling through the rock as the dets went off. This followed a terrific Wuummpp of the blast down our tunnel, and off we raced to catch the cage.

It was quite an introduction to mining. That night in bed all I could hear ringing in my ears was the tinkle of steel on granite. I spent a week with Dennis and mercifully his regular partner came back. I had mixed feelings about this as working with a machine man made a huge difference to one’s pay packet. The contract normally being split 60/40 between the two partners. My few days with Dennis netted me £40 extra. I went back to the OC work but little by little I became known as a good spare man and worked a day here and there.

Dennis’s raise was quite a big one, about 6ft square in cross section between two levels. Sometime later I was on a crew lowering and connecting steel drainage pipes down the raise, from the 290 fathom level to 320. We were surprised to find a £50 bonus from that job from parsimonious old Crofty. The best bit was that we were paid in cash, it was nice to count the £5 notes on pay day.

Another unforgettable day soon came along when I was sent in to help Walter Miszkiewicz. He was one of the several Polish miners who stayed in Cornwall after WW2. Walter was mucking out several piles of dirt from box holes and inters. (The openings that would eventually hold timber chutes that bled ore from the stope above.) As normal he was in a furious mood, working like a demon. The mucking machine, known as an Eimco 12B rocker shovel, was being hurled backwards and forwards on its track. Together with the ear-splitting howl of its compressed air motors.

Together with Bob Leatham in lieu of an electric loco, my job was to push the filled wagon out to the cross cut track switch and bring in an empty wagon. Now and again the mucking machine would bounce off the wonky track as the bucket swung up and over with its load of rocks. Then with his curses adding to the din Walter would jam a drill steel under the machine, drive it back so that it rose in the air and we would shove the beast over and back onto the rails. At this point it was best all round to stand clear.

Finally mucked out and the dust and fog and noise subsided, Walter would become quite human again and we all sat down on the crib seat for a chat. In between such bursts of maniacal work Walter would squat on his heels. Rolling a cigarette talking about the war or Argentina where he grew up. This was a taste of things to come as I later became Walter’s regular partner for months.

The flip side to the early start, going underground at 6.30 am, was that we came up at 2.30 pm. Soon showered and changed I made my way home in my little Bedford van and drove back to St. Agnes. Always checking out the surf en route at Porthtowan or Portreath. As summer approached I left the mine to lifeguard at Chapel Porth beach. This was fairly normal for the unskilled work force at South Crofty, people came and went. But as the shadows lengthened over the cliffs in September I was rehired by Herbie Hattam who understood that lifeguards needed winter work.

I was soon back on the OC gang on the 310 level, operating from our crib seat in the main cross cut. We all gathered for croust time for a sandwich and coffee out of a thermos and were back at the shaft station by around 2.00pm to wait for the cage. The lower levels were cleared first so that a cage full of miners would swish past with a ragged cheer. Then at last the cage would silently slide to a halt at our level. The cage tender would open the gate and leap aside as there was a rugby scrum to get in.

The cage had a small lower level about four feet high where sometimes the machine men would get in and sit on their det boxes. Then the cage dropped a little under the control of the cage tender and the rest of us would pile in. Unshaven faces inches apart, cap lamps turned off. Then swish up past other dimly lit stations to daylight. The trip down in the morning was usually more pensive, often eager to get down out of the cold. Maybe just the odd joke or Jimmy singing Methodist hymns, his deep voice echoing up the shaft. Then we stepped out under the dim light of a single bulb to start a new day. Cornish Miners Memories 4

Within a few days I was back with Dennis. His regular partner Earl from Jamaica must have decided my return was a good time to have some time off. This time Dennis was driving a tunnel, or drift, on No.9 East. The 9th was the furthermost lode from the shaft and therefore the hottest. Hot water poured from the granite above us. I worked in a pair of shorts, trying to lay track on sleepers that were floating around. Dennis’s feud with Herbie led us to being moved to another distant drift in the TinCroft area. About a two mile trek from the shaft and soon after that Dennis quit and went to sell cash registers.

By now all the personnel were using Robinson’s dry and shaft. The lower levels 360 and 340 were given to the Cook’s men and the upper levels 310 and 290 to the Robinson’s men. So we ranged far and wide over both sides.

This was my longest period of employment at Crofty. From September to the next lifeguard season I worked with a number of people. Freddy Roslin was another Pole who was blasting close to the shaft station. Anyone coming from Cook’s side at the end of the shift waggled their cap lamp at him to let him know they were safely past before he could blast. That was about the limit of safety procedure. Meanwhile about a dozen men were sitting at the shaft station trying to look casual, knowing that a terrific blast would go off any minute.

A friend of mine from St. Agnes, Charlie, was there on his first day underground and nobody told him what to expect. When the blast came Charlie hurled himself to the ground as if the entire mine was about to cave in and of course we all laughed uproariously. One day I was working there with Freddie and after we charged up and pressed the button on the exploder nothing happened. I walked back to the shaft station where a large number of men were sitting in silence with a finger in each ear waiting for the massive explosion. I quietly said to all “Has anyone got a tester?”

Following that uproar of relief I went back in to Freddie to start the nerve racking job of testing the connections on a very live round. Freddie had a red sports car, a Triumph Vitesse. He took it back to Poland, still behind the Iron Curtain, to impress his relatives each summer. One other thing I remember about Freddie was that he came to work one Monday morning in a sparkling white Naval Officer’s tropical suit. We all wore old clothes that soon rotted out in the mine water. By the end of the shift of course Freddy’s suit was completely ochre-stained. Cornish Miners Memories 4

There were two Sicilians on our level, Charlie and Angelo, who worked as trammers.Pulling the chutes and dumping a string of mine wagons down the ore passes. Also nearby were Joe Amenda with whom I worked in an underhand stop for a few days, mucking out inters with shovels, and Mario. Joe was a short but strong little Sicilian whereas as Mario was a big, good looking but very terse man and not a joy to work with. I had a few days with him drilling and blasting box holes.

The art of being a good partner to a machine man was to anticipate his needs and hand him what he wanted. For example the right detonator for the right hole, or to collar the next hole without his having to turn off the rock drill for instructions. Mario was uncommunicative and his English was minimal. Because the cost of gelignite came out contract pay he expected me to fiddle extra sticks of gelignite from under the watchful eyes of the shift boss. Cornish Miners Memories 4

He would be bad tempered all day. Then as soon as the round was fired would be beaming happy. It was possible to drill and blast more than one box hole a day. Climbing up and over one muck pile to get to the next, the piles of dirt reducing any possible ventilation and creating a hellish workplace. At the top of the box holes the inters were driven. Quick to drill out as they were narrow but often barely room to turn a short-handled shovel. Once they were in so far a wheelbarrow was needed to muck out. Cornish Miners Memories 4

Peter and Henry were another pair of older Polish miners who had worked together for years. It was rumoured that Henry had fought at Stalingrad. Peter suddenly had a heart attack, luckily not at work. So I was sent in to work with Henry. He was driving an ore pass at a 70 degree inclination. With just a chain ladder to climb on it was a work place that demanded respect. There were no harnesses or safety gear and one slip would have been fatal. Henry was a slow, silent and careful worker and I survived a week or more with him until the raise broke through.

All his was a prelude to working with Walter. I started off with him in a raise and, being Walter, it was no easy raise. It was driven ‘on load’ and in the middle, some way up by now, the stringer of ore pinched out. Walter had taken a couple of horizontal rounds to create a cuddy and then the raise set off in a new direction. Thus creating an almost impossible climb with a drill steel stuck in a hole to walk across, a typical Walter innovation.

Things reached a crisis one day when the climbing chain was blasted down and somehow Walter climbed up in his old Wellington boots to replace it. The process was the same as raising with Dennis but always fraught with difficulty. The worst bit of the day for me was climbing up the raise one handed with a 50 lb box of gelignite on my shoulder. Cornish Miners Memories 4

On one occasion the box burst and scattered gelignite all down the raise and I think I outshone Walter for oaths. Just when I could barely face another day of increasing difficulty. Walter greeted me in the morning with the news that it had broken through. So we had an easy day moving all our gear on a wagon chassis up to the next level to clean up the breakthrough and start a new drift. The first couple of rounds in had to be hand lashed, ie mucked out by hand with a shovel. We would take turns to load a one ton wagon and push it out of the way with a somewhat competitive edge.

Walter was about 50 and very fit, lean and muscular, despite the skinny roll ups he smoked. I was 24 and as fit and strong as I’d ever be but the work would leave us both gasping. With the drift started one morning Walter arrived bearing a hacksaw blade and a knowing look. We had to spend a long time cutting the two rail tracks and begin putting in a switch. With the switch established we could start drifting and laying our own track. Some miners preferred to just drill and blast and have night shift muck out and lay track. Walter being Walter chose to do it all ourselves.Cornish Miners Memories 4

So with Walter set up and merrily drilling away I would start digging out small trenches for the wooden sleepers in the muck on the tunnel floor. If there was sufficient dirt that could go alright, with a lot of sweaty pick work, but if there was solid rock in the way it was hard to get the sleepers down level. Often the granite had to be split out with two picks. Once the sleepers were down a pair of rails was laid. Sometimes a slight bend put in them with a jib craw, the fish plates were bolted up and the rails dogged down with track spikes. Two on the outside of each rail and one inside at each sleeper.

A pair of old short rails were laid on their sides to run the mucker in against the muck pile after the next blast. Of course these could get out of alignment and cause all the accursed derailment of the mucker. When this drift got going properly Walter seemed to be going for some kind of record. We would muck a four foot round and drill a six. Then next day muck a six and drill a four, plus lay track and extend pipes. By the time I’d driven in the loco and a string of wagons in the morning Walter could be already be roaring into it with the rocker shovel, cleaning up the track. Cornish Miners Memories 4

It would not be unusual for Walter to be still drilling at 1.00pm. Iwould be loading gelignite and safety fuse alongside him, a dangerous and illegal practice. By 2.00pm Walter would be lighting up the fuses like a firework display. Old Jack Jarvis who worked farther in walking past the end of our drift shaking his head in disapproval. Also I would be hurriedly backing out of the drift as the seconds ticked by. Cornish Miners Memories 4

At one stage I helped Walter drill long holes from the top of a short raise up into an old flooded portion of East Pool in some dim and distant part of the extensive workings. Each hole was plugged with a wooden bung until we had half a dozen holes finished. Then came the day when we had to knock out the bungs, As the flow of water increased to fire hose proportions I started to feel like a rat in a drainpipe in a thunderstorm. The shift boss sent us home after that inundation. I promptly went down with a chest infection akin to pneumonia, needing a week off and penicillin. Cornish Miners Memories 4

Unbeknown to me Walter was off for the same week with the same problem. We probably caught it from the water but back at work on the following Monday nobody offered any enquiry or even sickpay. During my first period at Crofty as a Cornish Miner I worked with Frank Davies, an ex-Navy man and pleasant Mancunian. He was drifting with night shift mucking and laying track so our days were relatively straightforward.

I was standing at the face one morning, the Thursday before Easter. Collaring a hole when a slab of granite fell squarely on the top of my helmet, broke in two and cut my left arm and right shoulder. That weekend I drove to Lancashire and felt very tough when my girlfriend tended to my bloody bandage. Frank needed a reconditioned motor for his Ford Cortina so I volunteered to drive up to London after work one weekend to get it. He gave me £50 and some petrol money. So off I went, spending the night at a friend’s place and finding the garage lock-up the next morning.

June 7th arrived and I was ready for a short stint as lifeguard and a surfing trip to Biarritz. I felt quite sorry to be leaving Walter as we had become as close to a team as anyone could with the erratic and difficult character. Also we were making good money, albeit hard-earned. I would miss Crofty too as the work was satisfying and time went fast underground. Cornish Miners Memories 4

I would miss driving to work in the pink dawns. With the warm smell of the dry as you stepped in out of a cold morning. The Cornish humour of men like Puff, the one-armed dry man and Jimmy who sang in the cage. Standing outside waiting to go down in the clean morning air in starlight or early morning sun as the year progressed. The sudden cosy warmth as the cage dropped out of a wet windy morning.

Also the camaraderie of two men toiling in the roaring fog of a drill face driving a way through the living granite by their own sweat and toil. The revival of a hot shower after a hard shift all these remain as pleasant memories of that period. I left on that last Friday with a fat pay packet not knowing I would be back three years later.

I spent three years at Camborne School of Mines, arriving at Holman’s Test mine on day one with my boots laced up with blasting wire. In the summer vacation of our second year I worked in a mine in Idaho. The Bunker Hill lead zinc silver mine in the Bitterroots, part of the Rocky Mountain chain. That trip by Greyhound bus and two months underground was a story in itself. With CSM all behind me and emigration to Canada in the pipeline I went back to Crofty to beg some work.

By now things were tight. I had a week in the mill shovelling spills from conveyor belts and then managed to get a job underground again. I worked on 360 level on Cook’s side to which we had a long walk every morning. One of us had to take the machine men’s drill steels in every morning on a mine car chassis, an innovation from when I carried ours on my shoulder. It was an uphill push to the half way point and then by running and jumping on you could free-wheel to Cook’s, risking the tight curves. Then arriving with a clattering crash at the crib seat where eight or ten of us sat before and after work and at croust time.

Walter was there, no longer drilling but relegated to mucking out old stopes with his fat jovial partner Treive, dusty, dangerous work. Work with machine men was scarce for us OC’s and for a bit of bonus, £5 in fact. We would some days remove a set of old track from a particularly hot and dusty old drift, struggling with rusted fish plates and bolts. Every three days or so a pair of us would lay a set of track behind a young machine man who was drifting in Amazon conditions. A mixed blessing as we got £7.50 bonus for a day of misery and effort, gasping after a 10 second burst with a pick or shovel, all with the drill roaring, feet away.

Back at the crib seat there was quite a crowd of us and we organised a party there for Christmas Eve croust time, with a small tree and decorations.

In the event I had to go work that day with ex coal miner Fred in a sweltering box hole. I managed to get the last chocolate biscuit when I came back for the gelignite. I worked with Fred for my last few days underground. He was an organised worker and we had time to talk about pit ponies and coal mining in our breaks. We were 30 feet up in a vertical box hole working on a plank stage and in haematite ground. So when we came out at the end of the shift we were completely covered in ochre.

My last day was in the New Year, 1975, and as usual I was glad to reach surface that afternoon without broken bones or cuts. Or a fatal fall of rock like the one that took my great grandfather. Years later, on rare visits back to Cornwall I couldn’t drive through Pool without looking over at the head frames of Cooks and Robinsons and remembering the roaring gloom of working deep in the Cornish granite, with the Cornish Miners.