South Crofty Mine Underground 1: This is the first page of the New 20 Galleries of images that I took during my underground visits to the working South Crofty Mine.

I have gone through the negatives time and time again to ensure I have not missed anything, consequently this is the final effort. My darkroom skills have improved over the years so I can now print images I have been unable to do in the past. Many long hours have been spent in the darkroom to reach this stage. Every image has been reprinted to the best of my ability. So many of the negatives were out of focus which was a shame.

The following pages have been roughly sorted into different themes ie Stoping, Diamond Drilling and in some cases to different locations and activities. I have tried to be accurate on my information tapping many Ex-Miners for help and locations.

I hope these new pages will provide a fitting memory to the people who worked at South Crofty Mine, and to the Cornish Cousin Jacks all over the world.

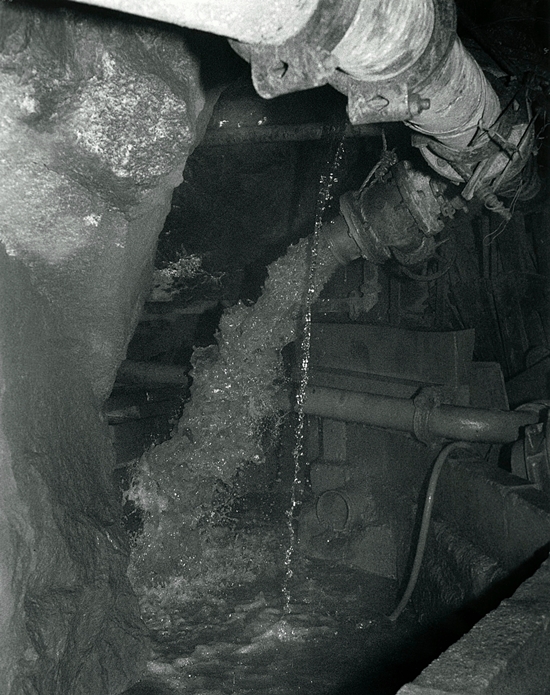

This page looks at the Shafts of the Mine along with the Shaft Stations and the constant fight with the water in the workings.

I have received an account from Stu Peters an ex-South Crofty Miner about a particularly bad day at the Mine. It is well worth a read:

During the autumn of 1973 I went to work at South Crofty. On my first morning I rode the cage down to 380 at Robinson’s and met our shift boss John Gidney. He walked me along the level, showing me what went where, and how the system worked. He told me that I was to work on the spillage crew. I hadn’t a clue what he was talking about.

Finally we reached Cook’s Kitchen side he introduced me to the other members of the Spillage Crew, Charlie Merton, Adrian Roberts and Steve. To my shame I cannot remember Steve’s surname. We had a chat and Steve showed the way down the ladder way to the sump before instructing me in what seemed a pretty simple job. Apparently Mine Captain, Eddie Leake had found some difficulty in recruiting a full spillage crew and my arrival had been fortuitous.

My 3rd day at 6.30am, found me at Cook’s Kitchen waiting for the cage down to 380 fathom level. I was dressed in a an old tweed jacket, swimming trunks, boots, helmet, lamp and battery. This was attached to a belt round my waist with the battery being carried on the belt adjacent to the small of my back. I also carried a gallon of water in a plastic container.

I was accompanied by the three other members of the crew. Charlie Merton the winch driver, Adrian Roberts the fellow who made sure that the spillage re-entered the system and Steve who worked with me in the sump. It was a little draughty standing about under Carn Brea on a cool autumn morning. On entering the cage the heat was like a balm, the warm, wet air, steaming as it rose from the depths.

Upon alighting from the cage on Cook’s shaft 380, the lowest working level in those days, you would see the Crusher in front of you and a few yards away. This was a brutal machine, its jaws smashing the large rocks down to a max of 8 inches. It shuddered now and then as it grappled with large, recalcitrant individuals of the rocky race. On the left an ore pass funnelled the ore to the crusher. Two and a half ton Granby wagons hauled by diesel loco’s stopped after their loads were tipped into the ore pass.

The air was filled with the fumes of diesel exhaust. To the right there was a floor mounted electric winch with a steel cable that stretched upwards at 45 degrees. This passed over a pulley and down to a one third of a ton capacity steel kibble hung over an adjacent shaft that had been sunk to 400 level. Just beyond the kibble was a ladder way that led to the sump.

I had heard, listening to gossip, that there was some concern that the spillage was building in the box to the extent that it might hamper the lowering of the ore skips. Cook’s Kitchen shaft had been sunk to the 400 level to facilitate the filling of the rectangular steel ore skips that would descend from the surface and stop just under the outlet from the crusher. The ore was released into the skips until full before being raised to the surface for onward transmission to the ore bins.

This was not a precise operation; the ore skips sometimes received a little more than they could carry. The extra ore overflowed and tumbled into a vast box constructed of wood that extended 120 feet from 380 to the floor of the sump at 400. Basically, a brattice to enclose the spillage. It was our job to remove the the spillage from the box so that none of the ore would be lost and to ensure that the skips could still fit into the box without being obstructed.

The adjacent shaft had been sunk to 400 before a chamber (the sump) could be developed to facilitate the reclamation of the spillage. The sump was approximately 20 feet wide across the shafts by 15 feet deep with the back being some 8 feet above the floor. A ladder way was constructed to allow the ingress and exit of the two spillage crew members who would carry out the reclamation.

Standing in the sump and looking at the western wall, the ladder way was on the left. A rectangular pit about 4 feet deep had been sunk between the ladder way and the south face of the brattice which extended some eight feet from the western wall. The box extended to the northern wall. A steel door (spillage chute) had been let into the south facing side of the brattice just above the pit. The door could be opened and closed by the turning of a large steel wheel attached to a horizontal shaft that was geared with cogs to raise and lower the door.

Steve and I would take it in turns to hop down into the pit and receive the kibble which would be swung across and pressed tight against the pit wall below the door. The door would be opened, the bucket filled with spillage the door closed. Two tugs on the cable and the bucket disappeared up the shaft for Adrian to recycle. Cook’s side was warm and the sump was probably the warmest place in the mine. Caused by geothermal heat and water combining to form a hot and humid atmosphere. There was an upright conical, blue electric centrifugal pump in the pit to combat the ingress of water.

I took my turn in the pit, received the kibble, pushed it into position and waited for Steve to open the door. I suddenly received a ‘God Send’; a patter of small stones and dirt fell on me. Steve roared at me to get out and I was glad to have him grasp my hand and help me pull myself out of the pit. I caught a glancing blow from a heavier stone on my shoulder.

As we ran back to the furthest point of the sump we could hear the crashing roar of an avalanche. We turned, and in the beam of our lights saw a cascade of stones. Huge chunks of dirt and rocks filled the pit as the timbers above the door gave way. The avalanche was spreading along the western wall. It eventually swallowed the ladder way and crept towards us until it slowed to halt.

We moved carefully over to the base of the pile of rubble where the ladder way used to be. A glance upwards with our lamps showed no sign of the ladder way, nothing but fallen rubble. We were trapped.

We stood at the foot of the pile of rubble, shouting before waiting to hear voices. Hoping that the ladder way could be negotiated far enough from above to allow us to hear some verbal communication. We heard nothing and retired to an old duck board that served as a croust seat.

I think we were in shock for a while and did nothing as there appeared to be no immediate solutions. Fortunately neither of us panicked and we decided to move to the foot of the avalanche with the intention of manually removing rubble that covered what should have been the ladder way. We worked away for an hour or so I suppose, being careful not set off a further fall, stacking the rubble behind us.

We started feeling sharp tingling sensations when we touched the water that had been steadily rising. We soon realised that the electricity cable to the water pump in the bottom of the pit had been severed. We had no way of asking those on 380 to ensure that the power was turned off. This was not good; we were powerless to escape from the sump.

We sat on the croust seat to swap stories to entertain each other. After a while we were obliged to prop it on some rocks to bring it clear of the water. We turned off our lamps to save the batteries and sat together, chatting in the absolute darkness. Sipping at our water containers; the heat and humidity were debilitating.

We used our lamps from time to time to check on the water level which was now creeping up our boots. Unbelievably, we both dropped off to sleep for a while. I woke and wakened Steve and we discussed this phenomenon, perhaps it was the heat and humidity. Maybe carbon monoxide seeping from the rocks that had been blasted with dynamite from the solid rock face. We had lost all track of time by now.

At last we heard a muffled shout and we sloshed over to the rock pile keeping well away from the pit. We heard ‘Are you okay?’ and shouted back, ‘Turn off the water pump’. All was silent for what seemed an age before we heard. ‘Okay, it’s off’. We gingerly tried the water nearer the pit with our hands and found no tingling.

We went on removing the rubble at the site of the former ladder way while our rescuers were moving the same from the top. As they made their way closer we could communicate and work together. The water kept rising, no faster though. Eventually a rope was dropped to us and our rescuers helped us pull ourselves up to safety on to the lowest undamaged platform of the ladder way. We were pleased to see Charlie and Adrian with a few other miners who had done all they could to get Steve and I out of trouble. Great guys, all of them.

I don’t remember much of the rest of the day. I handed in my lump and light, showered, dressed and went home. I was surprised to find that it was getting dark outside, seemingly an age since I had been at Cooks 380 at 6.30 that morning. Because there was an urgent need for repairs no ore could be lifted until the spillage situation was attended to. So we were redirected to repairing the track on 380 followed by draining the slime bays.

This was not the best job in the mine. We stood in mud and warm water literally up to our necks in an underground pond while opening a tap in the back. Located just above our heads so that slime could be released (all over us) from the slime bays above before turning the tap in the opposite to send a blast of fresh water upwards and keep the tap clear of debris. Fortunately, after a day of this we were reassigned to the now repaired spillage operation. Steve had moved on and I had a new companion in the sump.

I left the spillage crew in in the New Year to broaden my knowledge of the South Crofty operations and went onto the night shift. Here I trammed with Reggie Laity up on 240 fathom. It was bone dry but hard to make any money and daylight was becoming a memory. So, in the spring I went on with Master Machineman Mike Osman. We were raising on 380 fathom, I loved it, challenging and good money.

However, I had the feeling that Crofty would not survive for too long. Huge alluvial deposits of tin in Malaysia were being drag-lined out at a fraction of the cost of us chasing a narrow seam of cassiterite 380 fathoms underground. Sadly, I said ‘farewell’ and moved on to another venture.

I loved my time at Crofty and it is hard to think that the sump and 380 are almost two and a half thousand feet under water. But it is a long time ago and I wish all the best to anyone who is still around and recognizes himself in this story.

Stu Peters.

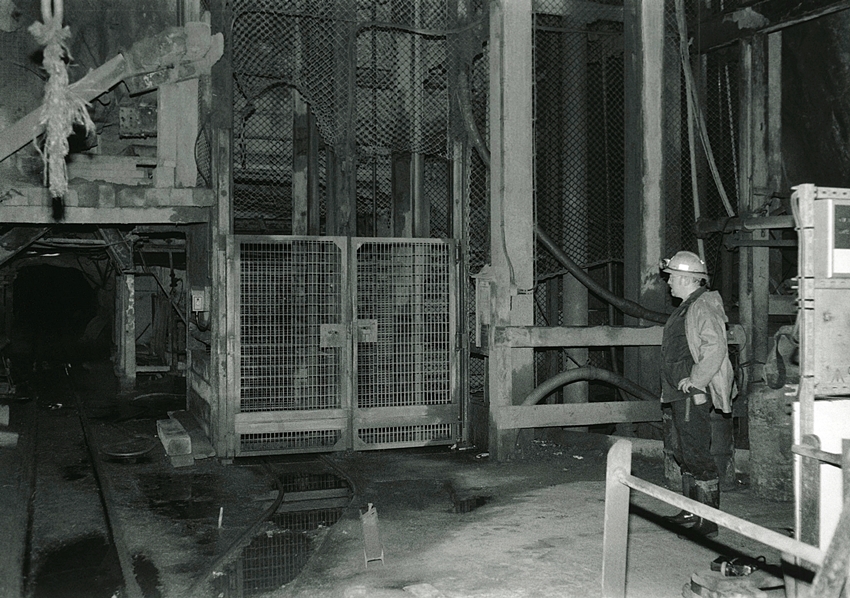

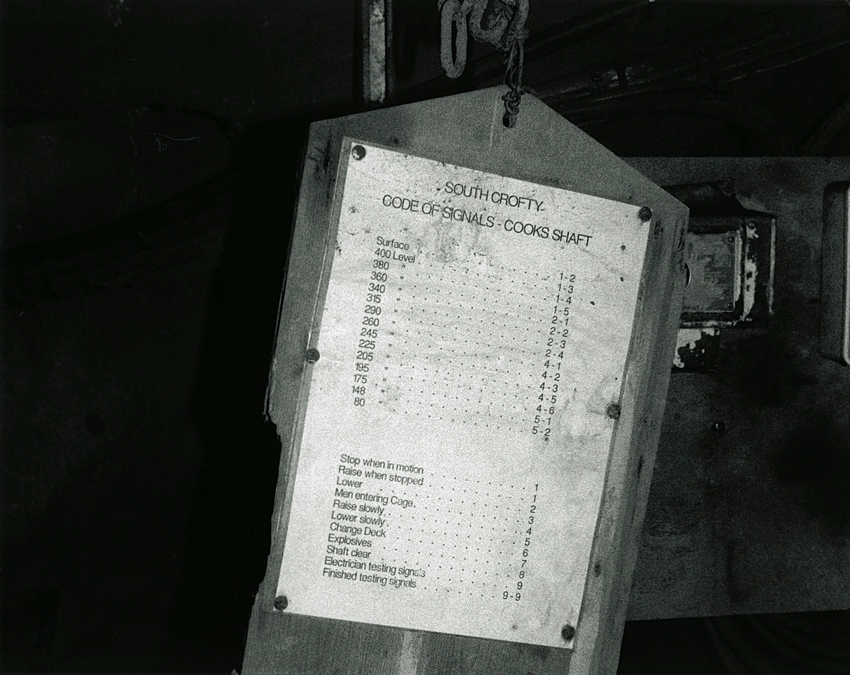

The next few images are of Robinson’s Shaft stations. The sinking of Robinson’s Shaft commenced in 1901 when it was decided a new vertical shaft was required to expand the mine. This was the primary access to the workings for most of the 20th century.

By 1993 all man riding was through Cooks Shaft with Robinson’s as secondary access. At 160 Fathom Robs passes into a big open stope. The passenger didn’t see this as the shaft was shuttered, effectively suspended in empty space. It’s actually the junction of two stopes with a ‘tooth’ of rock suspended between the two.

The problem was that the tooth was moving, as a precursor to collapse. Consequently the whole shaft would be unusable, hence the abandonment. If and when the tooth does snap off it will feel like a mini earthquake on the surface.

Notes by Nick Le Boutillier.

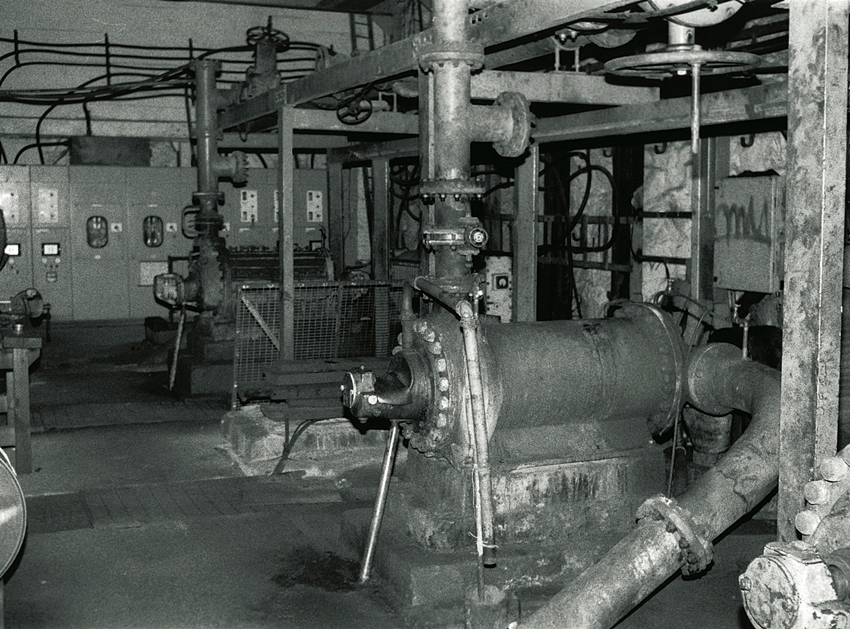

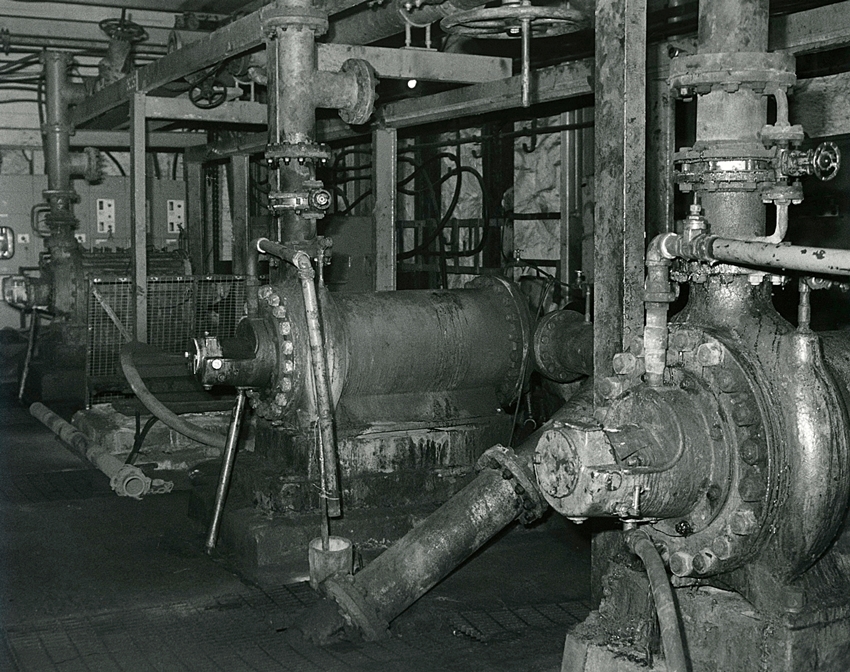

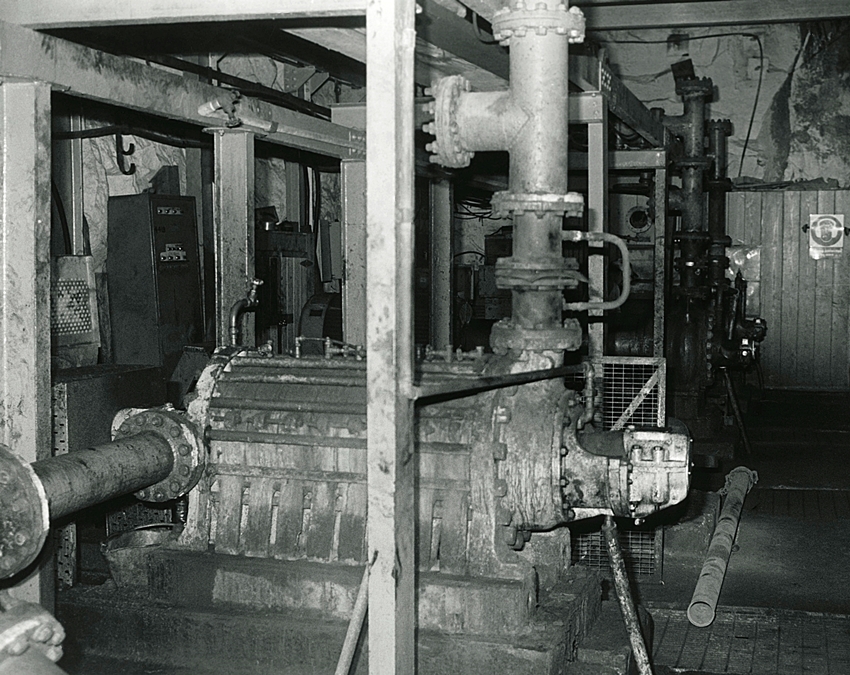

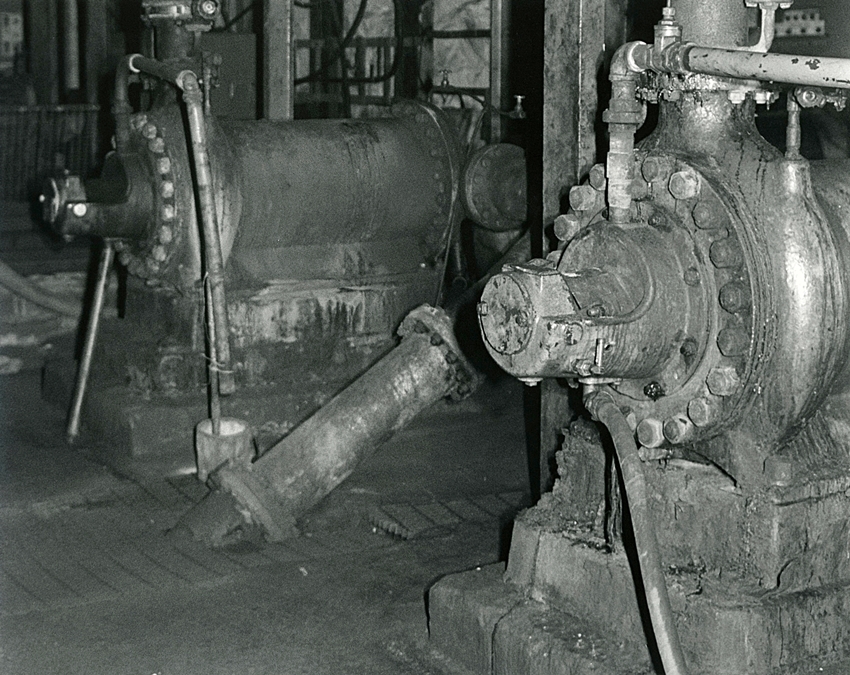

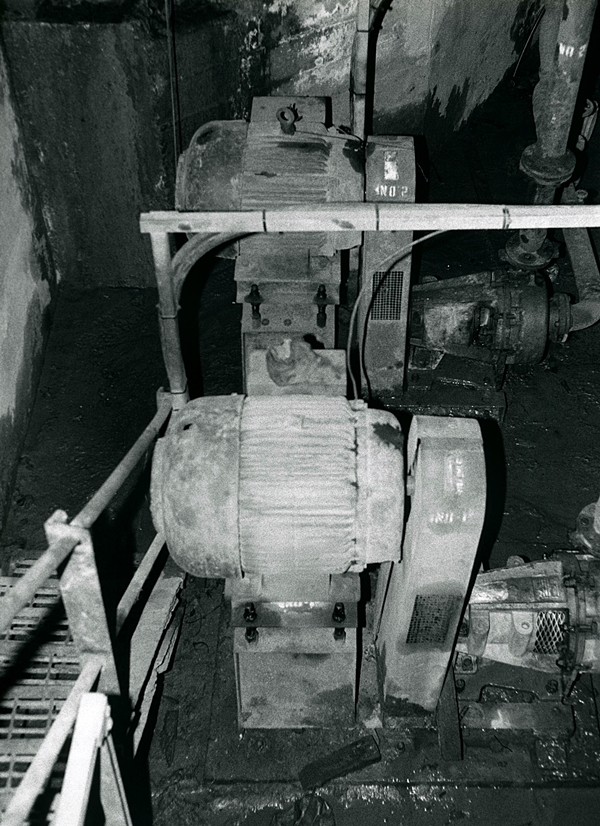

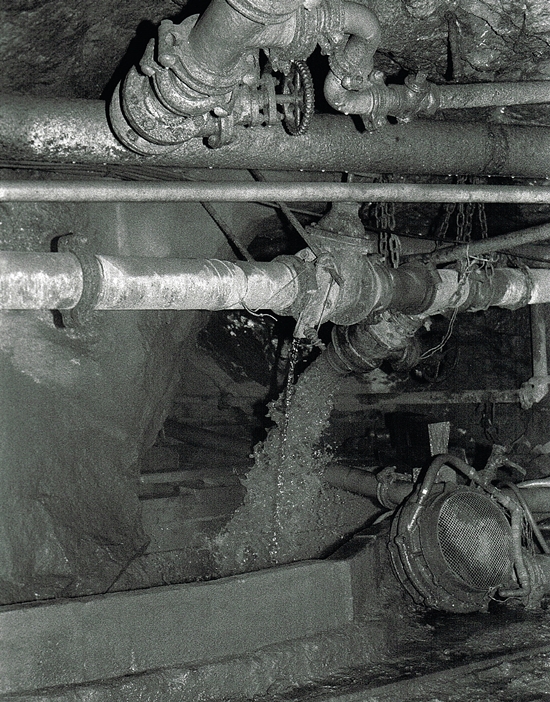

The remaining images on the page were taken in the underground pump station on 195 Fathom Level of South Crofty. Water was the biggest enemy of the mine, when the pumps stopped the lower levels would start to flood. The pump stations were at Cooks 195, 340 and 400 Fathom Levels. These pumps would handle approximately 1.5 Million gallons per day.