These pages Cornish Miners Memories, are here to capture and preserve some of the memories of working underground. I have asked several ex-South Crofty Miners if they will put pen to paper and describe a typical (or non-typical) day at the Mine. When time is available to them, many said they would give it a try.

On the next few pages are the accounts of several miners I have received.

They have my thanks.

If anyone who has worked in Cornish Mines would like to contribute to this page please contact me. I really would like this page to work, I had many visits to South Crofty. I did experience some of its unique atmosphere but I was an outsider.

So join me on a trip down New Cooks Kitchen Shaft, into Miners Memories.

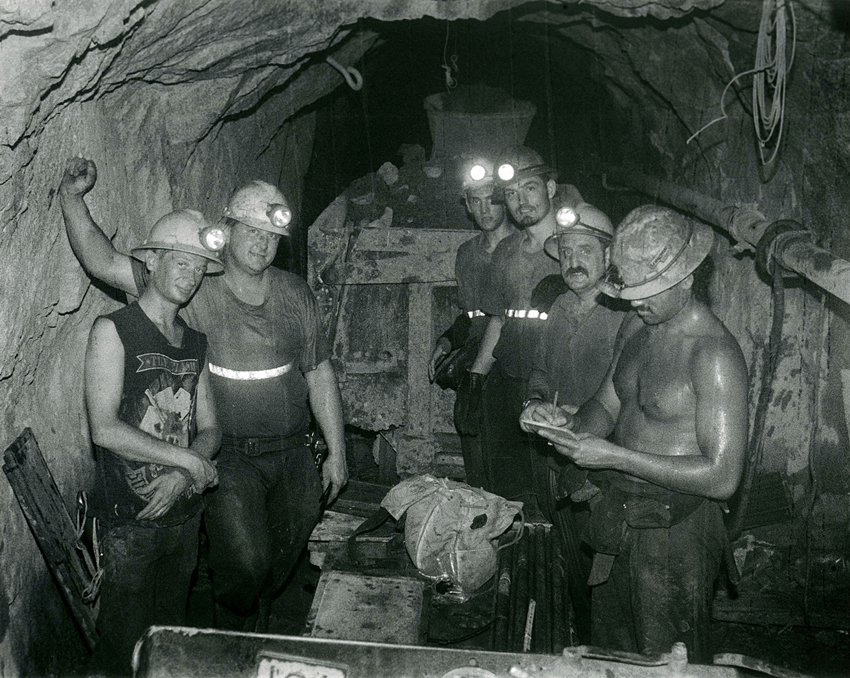

The first contributor to Miners Memories is Martin Wolstenholme who worked at South Crofty Mine from 1978 to the mines closure in 1998. This is his story in his own words, I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I did, his Miners Memories:

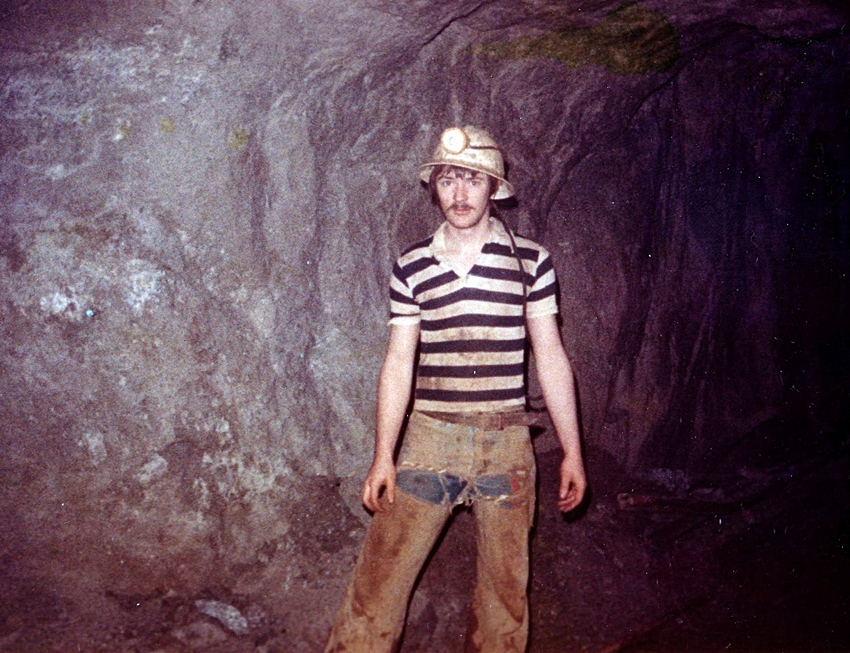

My father, Dennis, worked at South Crofty for nearly 2 years before I started there. He used to describe the heat and humidity, the various machinery and tools, the noise and the smells. However, nothing could have prepared me for what it was really like underground. It was February 13th 1978. I was eighteen, barely 10 stone in weight and not the beefiest of young men.

On my first day I travelled down Robinsons Shaft with the Shiftbosses and two other new workers, Dave Dunstan and Duncan Judge. Once we got out of the cage on 335 level. I knew at once that I was a little over-dressed wearing a thick knitted pullover that my mother had taken a very long time to make. It was quickly discarded, never to see the light of day again! Just the relatively short walk to Les Hockings’ Shiftbosses hut was enough to bring the 3 of us out in pools of sweat. After a cup of coffee from our flasks and a ciggie we accompanied Les on his round of supervision.

We met a group of what were called O/C men (Owner’s Commission) who were doing some track maintenance. O/C men were general underground labourers who did a bit of this, that and the other whilst waiting/hoping to pair up with a good leading miner. Many of the Drives (tunnels) were named after the miner that drove them. One of the first drives I seem to remember was William’s Drive named after Clive Williams, a midlander living in St Ives. He also happened to be me and my father’s lift to and from Crofty.

Along this drive Clive had a Stope and he and his partner, Dave Partridge, were having their rearing chute pulled in order that they could mine the next lift over the ladderway. The stope was about a third mined out so the ladderway would have been about 50 feet high. I followed Les almost to the top of the rearing and could hear him chatting to Clive and Dave. I had no idea that the rearing chute had ‘hung up’ because suddenly the dirt collapsed creating the most almighty noise as it hit the rearing boards. It scared the wits out of me. Oh how they laughed!!

On the second day, Andy Bennie, who was the Mine Captain of the middle-section of the mine asked me if I had any religious convictions. So when I replied ‘no’ he told me that the guy I was going to be put to work with was a Mormon – Arthur Harris. Arthur was a timberman and I was to learn my trade from him. Now don’t get me wrong, he was an ok sort of bloke but did he bang on about God? Yes he bloody did! So annoying at times but it spurred me on to try and become an O/C man or a trackman just to get away from him.

During these early days I was working in Roskear on 340 level, building chutes. Arthur, Tye Steadman, David Jewell and myself were the timbermen, Alan Thomas and Contrino were the trammers (there were a few italian miners at Crofty and some of them were known by their surnames only). I’m not too sure who the stopers were at that time but some of the miners on 340 level were:

Peter Hughes – Shiftboss.

Jimmy Clemence & Dennis Brown.

Dennis Evans & Alistair Rule.

Johnny Allen & Michael James.

Johnny Ashworth.

Charlie Flood & Keith Mitchell.

Within the first fortnight I had my first experience working with a machine man . . . .but that’s another story for Miners Memories!

For production miners, particularly stopers, it was imperative that they were supported by ancillary workers, be it trammers, timbermen or even technical service support. The stopes created the majority of the income for the mine. Also a lot of development work was carried out in waste ground which gave no return for the expenditure, save that it allowed access to the ‘pay lodes’. So it was incumbent upon miners like me and Arthur to install rearings for the stopers as and when they requested them. This meant we had to drop the chute building work that we were engaged in in Roskear South and take our tools all the way into Dolcoath North on 340.

This wasn’t a 2 minute job as we had to load our trolley (basically the chassis of a 1 ton Hudson wagon) with our gear which consisted of:

•Air Chain-Saw

•Bow Saw

•Sledge hammers – 14 and 7lb

•Measuring staffs

•Lump Hammers

•Dags (small axes)

•3 & 6 inch nails

•Rearing shoes

As the crow flies Dolcoath North wasn’t so very far away from Roskear South. But in reality it was probably the best part of a mile through the levels workings. There were several designated storage areas for timber on the level, generally in an airy location as so that it could dry out.

We would stop off to load half a dozen 8” x 3” x 14ft boards and a couple of 8” x 6” x 14ft bearers and hand-push the trolley towards Dolcoath. The journey would take us to the main 340 crosscut, down towards the shaft and then on into the Dolcoath workings. However one has to remember that the drives were not completely flat, in fact most drives were driven on a slight incline of 1:250 thereby allowing the mine waters to drain towards the pumping station.

This incline worked in your favour when heading back shaft but it was a different story going away from it. It was really arduous work pushing a not insignificant load all the way into a hot end. If we were really lucky and got our timing right, we might meet up with the Dolcoath trammers (Telfor Simmonds and Kenny Trengove) as they were dumping their wagons down the ore pass close by to 340 station.

This would be marvellous because it would mean we could hook our wagon up to their loco and get a lift into Dolcoath. Heaven. If we were unlucky though we might have pushed the gear half way in and then met the trammers on their way out. This meant we had to off-load all our materials and tools on to the side and then tip the trolley onto its side to allow the trammers to pass before reloading and pushing on.

On some rare occasions we were really unlucky and having given way to the trammers already the next thing we knew there would be some track men coming towards us with their materials trolley. Again we would have to give way to these guys because their load was so much heavier than ours. A typical load for them would be:

•8 lengths of 35lb track (35lb per yard, 6 yards per length)

•Timber sleepers

•Fish-plates (track joiners)

•Dogs (Dog spikes)

•A Jim-Crow (track bending jig)

•Sword and vees (for shunts)

•Nuts, bolts and sundry other items

By the time we got to Dolcoath we would be pretty shattered and would have a breather before measuring up for the miner’s rearing.

The miner on this occasion was the legend that is Jimmy Clemence. Jimmy was and still is an absolute star! As a miner he had few peers, being able to turn his hand to all disciplines of mining. He was about 5’7” and probably less than 10 stone but my word he could make a rock-drill sing and dance. He made the machine work for him rather than the other way around. It wasn’t until a few years later when I was learning my trade on machines that I realised just how good he was.

Jimmy and his mate Dennis Brown had not long started this new stope. It was a reasonably sized ore body at about 2’7 to 3.0 metres wide and that meant the rearings were quite big and consequently harder work than rearings in a narrower stope. I’m pretty sure that we were paid a bonus of £12 between us per rearing installed (basic pay at South Crofty in 1978 was £56 per week but with daily bonuses a timberman could top that up to around £120-£130). Rearings were pretty straightforward in a new stope but as the stope got higher the work was so much harder as we had to carry the heavy timbers up some very steep and narrow ladderways.

The day after installing that first rearing, Jimmy needed a mate as Dennis had a days holiday. I suppose I must have made a good impression with Jimmy as he specifically asked that I work with him. Dolcoath North’s croust area was a fairly lively area first thing in the mornings as there were at least 6 pairs of miners working in close proximity to each other.

I recall offering a packet of smokes around and was alarmed that there were 11 takers! After what seemed like hours of drinking tea, smoking and chatting, Jimmy said ‘ I suppose we’d better go and make a start then’. I followed, as keen as mustard to see what real miners did. We washed and barred down the area of the previous days blast, making it safe to work under.

Then it was a matter of rigging up the machine (a Holmans 303 Rockdrill) the air and water hoses were connected. Get the oil bottle filled and we were ready to rock and roll. Jimmy told me what the plan for the day was. Estimating that he would probably drill 16 holes to a depth of 8ft in some benches in the middle of the stope. This was a breast stope and a few strategically drilled holes could create a massive volume of dirt once blasted.

Bearing in mind that stopers were paid by the cubic metre even though heights were still measured in fathoms. It was essential to break as much ground per hole as possible. Just before we started to drill, Jimmy asked me if I wanted to use ear defenders. When I asked him if he was going to wear any he said ‘No’. Not wishing to appear like a girl I declined his kind invitation. I was deaf for a bloody fortnight!! When other miners got to hear of my incapacity they rolled around laughing, knowing that Jimmy had a reputation for not being bothered by loud noises.

Today Jimmy is a little portlier than he was then and deaf as a doornail! I did enjoy that first day on machines though, and I learned a lot. One of the lasting lessons was never to rub your forehead if you have been handling gelignite ….oh my god. A dynamite headache is the worst, really, really awful. I believe it’s the nitro-glycerine that opens up your blood vessels and arteries. Years later we were to move away from PAG (Polar Ammonium Gelignite) and use ANFO (Ammonium Nitrate Fuel Oil) and Powergel which is an emulsion based explosive.

Two weeks after that day with Jimmy, he came up to me in the dry and said ‘64 64’. He could tell that I had no idea what this meant and repeated it slowly. ‘£64 and 64 pence’. This was my days pay. I couldn’t believe it, such a lot of money. A month earlier I was receiving £13.05 a week in social security. I would later discover that some miners, Jimmy amongst them, paid their mates 60/40. That is to say that the leading miner got 60% and the mate received 40%. So Jimmy was earning almost a hundred pounds a day in 1978. No wonder the other O/C men were pissed off that I got to work with him.

Thank you Martin this account for Miners Memories is very much appreciated.